When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in an eternity before and after, the little space I fill engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me, I am terrified. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me…

—Pascal

For thousands of years, whether poetry arrived in long stories like Homer’s The Iliad or brief songs like Sappho’s, there was no need to mark space on the page. In short, there were no line breaks. Economically, papyrus, animal parchment, were costly; literacy was exclusive; writing/reading still very much tethered towards communal recitation and performance when not strictly state laws and inventory. That doesn’t mean there weren’t lines, of course. The musical phrase, or metrical pattern, instructed the singer/reader where the pauses and breaks were to fall. And because these patterns happened in Greek verse regularly, the tongue and ear did a large part of the deciphering work. Anticipation was echo.

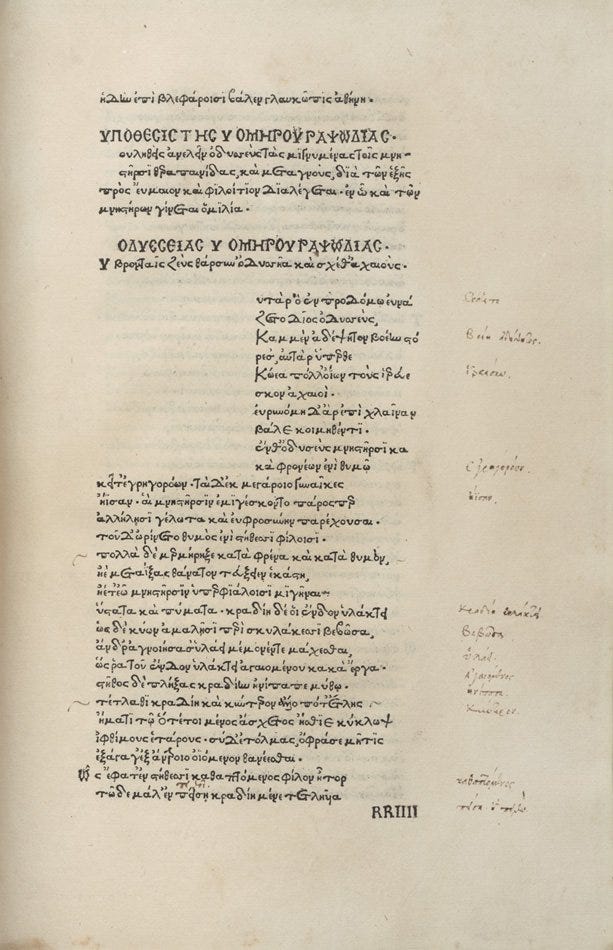

In the above images, on the left is a fragment of Homeric papyrus from the third century BCE. On the right: the first printed edition of Homer from 1488 CE. As you can see, the line breaks and vertical lineation have been added in the familiar form we find them today in most traditional poems. As the print age went on, the measure of breath (meter is such spacing) otherwise hidden in the text went from being purely a notational description—to aid memorization and recitation—to an essential element of pictorial space.