Your approach towards photography is very personal. Is not it a kind of therapy?

Yes, photography saved my life. Every time I go through something scary, traumatic, I survive by taking pictures.

You also help other people to survive. Memory about them does not disappear, because they are on your pictures.

Yes. It is about keeping a record of the lives I lost, so they cannot be completely obliterated from memory. My work is mostly about memory. It is very important to me that everybody that I have been close to in my life I make photographs of them. The people are gone, like Cookie, who is very important to me, but there is still a series of pictures showing how complex she was. Because these pictures are not about statistics, about showing people die, but it is all about individual lives. In the case of New York, most creative and freest souls in the city died. New York is not New York anymore. I've lost it and I miss it. They were dying because of AIDS.

You decided to leave the United States because of the effect the AIDS epidemic had on the community of New York gay artists and writers?

I left America in 1991 to Europe. I went to Berlin partially because of that, and partially because one of my best friends, Alf Bold, was dying and I stayed with him and took care of him. He had nobody to take care of him. I mean, he had lots of famous friends, but he had nobody to take care of him on a daily basis. He was one of people who invented the Berlin film festival. This was also the time when my Paris photo dealer Gilles died of AIDS. He had the most radical gallery in the city. He did not tell anybody in Europe that he has AIDS, because the attitude here was so different than in the United States. There was no ACT UP in Paris, and in 1993 it looked very much like in the US in the 1950s. Now it has changed, but at that time people in Europe told me: 'Oh, we do not need ACT UP. We have very good hospitals'.

Your art is basically socially engaged...

It is very political. First, it is about gender politics. It is about what it is to be male, what it is to be female, what are gender roles... Especially The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is very much about gender politics, before there was such a word, before they taught it at the university. A friend of mine said I was born with a feminist heart. I decided at the age of five that there was nothing my brothers can do and I cannot do. I grew up that way. It was not like an act of decision that I was going to make a piece about gender politics. I made this slideshow about my life, about my past life. Later, I realized how political it was. It is structured this way so it talks about different couples, happy couples. For me, the major meaning of the slideshow is how you can become sexually addicted to somebody and that has absolutely nothing in common with love. It is about violence, about being in a category of men and women. It is constructed so that you see all different roles of women, then of children, the way children are brought up, and these roles, and then men, then it shows a lot of violence. That kind of violence the men play with. It goes to clubs, bars, it goes to prostitution as one of the options for women - prostitution or marriage. Then it goes back to the social scene, to married and re-married couples, couples having sex, it ends with twin graves.

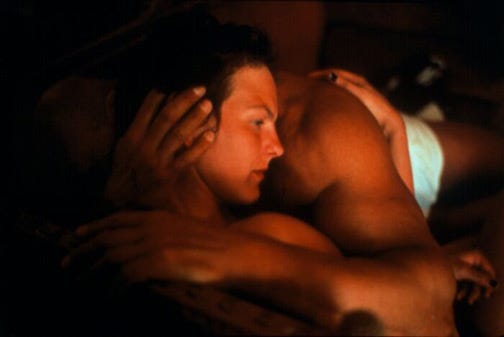

Nan Goldin - Valerie and Gotscho embraced, Paris, 1999, Galerie Yvon Lambert

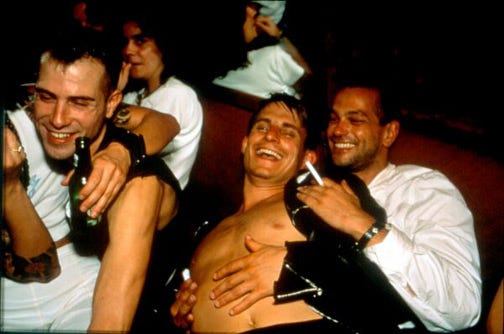

Nan Goldin - Clemens, Jens and Nicolas laughing at Le Pulp. Paris. 1999